Note: all the code in this blog post is available in my DemoCode GitHub repo, under Functions.

For most of 2020, one of the projects I’ve been working on is the .NET Functions Framework. This is the .NET implementation of the Functions Framework Contract… but more importantly to most readers, it’s “the way to run .NET code on Google Cloud Functions” (aka GCF). The precise boundary between the Functions Framework and GCF is an interesting topic, but I won’t be going into it in this blog post, because I’m basically more excited to show you the code.

The GitHub repository for the .NET Functions Framework already has a documentation area as well as a quickstart in the README, and there will be .NET instructions within the Google Cloud Functions documentation of course… but this post is more of a tour from my personal perspective. It’s “the stuff I’m excited to show you” more than anything else. (It also highlights a few of the design challenges, which you wouldn’t really expect documentation to do.) It’s likely to form the basis of any conference or user group talks I give on the Functions Framework, too. Oh, and in case you hadn’t already realized – this is a pretty long post, so be warned!

Introduction to Functions as a Service (Faas)

This section is deliberately short, because I expect many readers will already be using FaaS either with .NET on a competing cloud platform, or potentially with GCF and a different language. There are countless articles about FaaS which do a better job than I would. I’ll just make two points though.

Firstly, the lightbulb moment for me around functions as a production value proposition came in a conference talk (I can’t remember whose, I’m afraid) where the speaker emphasized that FaaS isn’t about what you can do with functions. There’s nothing (or maybe I should say “very little” to hedge my bets a bit) you can do with FaaS that you couldn’t do by standing up a service in a Kubernetes cluster or similar. Instead, the primary motivating factor is cost. The further you are away from the business side of things, the less that’s likely to impact on your thinking, but I do think it makes a huge difference. I’ve noticed this personally, which has helped my understanding: I have my own Kubernetes cluster in Google Kubernetes Engine (GKE) which runs jonskeet.uk, csharpindepth.com, nodatime.org and a few other sites. The cluster has three nodes, and I pay a fairly modest amount for it each month… but it’s running out of resources. I could reduce the redundancy a bit and perform some other tweaks, but fundamentally, adding a new test web site for a particular experiment has become tricky. Deploying a function, however, is likely to be free (due to the free tier) and will at worst be incremental.

Secondly, there’s a practical aspect I hadn’t considered, which is that deploying a function with the .NET Functions Framework is now my go-to way of standing up a simple server, even if it has nothing to do with typical functions use cases. Examples include:

- Running some (fairly short-running) query benchmarks for Datastore to investigate a customer issue

- Starting a server locally as a simple way of doing the OAuth2 dance when I was working out how to post to WordPress

- Creating a very simple “current affairs aggregator” to scrape a few sites that I found myself going to repeatedly

Okay, I’m massively biased having written the framework, and therefore knowing it well – but even so, I’m surprised by the range of situations where having a simple way to deploy simple code is really powerful.

Anyway, enough with the background… let’s see how simple it really is to get started.

Getting started: part 1, installing the templates

Firstly, you need the .NET Core SDK version 3.1 or higher. I suspect that won’t rule out many of the readers of this blog :)

The simplest way of getting started is to use the templates NuGet package, so you can then create Functions projects using dotnet new. From a command line, install the templates package like this:

dotnet new -i Google.Cloud.Functions.Templates::1.0.0-beta02

(The ::1.0.0-beta02 part is just because it’s still in prerelease. When we’ve hit 1.0.0, you won’t need to specify the version.)

That installs three templates:

gcf-http (an HTTP-triggered function)gcf-event (a strongly-typed CloudEvent-triggered function, using PubSub events in the template)gcf-untyped-event (an “untyped” CloudEvent-triggered function, where you’d have to deserialize the CloudEvent data payload yourself)

All the templates are available for C#, VB and F#, but I’ll only focus on C# in this blog post.

In the current (October 2020) preview of Visual Studio 2019 (which I suspect will go GA in November with .NET 5) there’s an option to use .NET Core templates in the “File -> New Project” experience, and the templates work with that. You need to enable it in “Options -> Environment -> Preview Features -> Show all .NET Core templates in the New project dialog”. The text for the Functions templates needs a bit of an overhaul, but it’s nice to be able to do everything from Visual Studio after installing the templates. I’ll show the command lines for now though.

Getting started: part 2, hello world

I see no point in trying to be innovative here: let’s start with a function that just prints Hello World or similar. As luck would have it, that’s what the gcf-http template provides us, so we won’t actually need to write any code at all.

Again, from a command line, run these commands:

mkdir HelloWorld

cd HelloWorld

dotnet new gcf-http

You should see a confirmation message:

The template “Google Cloud Functions HttpFunction” was created successfully.

This will have created two files. First, HelloWorld.csproj:

<Project Sdk="Microsoft.NET.Sdk">

<PropertyGroup>

<OutputType>Exe</OutputType>

<TargetFramework>netcoreapp3.1</TargetFramework>

</PropertyGroup>

<ItemGroup>

<PackageReference Include="Google.Cloud.Functions.Hosting" Version="1.0.0-beta02" />

</ItemGroup>

</Project>

And Function.cs:

using Google.Cloud.Functions.Framework;

using Microsoft.AspNetCore.Http;

using System.Threading.Tasks;

namespace HelloWorld

{

public class Function : IHttpFunction

{

/// <summary>

/// Logic for your function goes here.

/// </summary>

/// <param name="context">The HTTP context, containing the request and the response.</param>

/// <returns>A task representing the asynchronous operation.</returns>

public async Task HandleAsync(HttpContext context)

{

await context.Response.WriteAsync("Hello, Functions Framework.");

}

}

}

Right – you’re now ready to run the function. Once more, from the command line:

dotnet run

… the server should start, with log messages that are very familiar to anyone with ASP.NET Core experience along with an introductory log message that’s specific to the Functions Framework.

[Google.Cloud.Functions.Hosting.EntryPoint] [info] Serving function HelloWorld.Function

Point a browser at http://localhost:8080 and you should see the message of “Hello, Functions Framework.” Great!

You may be wondering exactly what’s going on at this point, and I promise I’ll come back to that. But first, let’s deploy this as a Google Cloud Function.

Getting started: part 3, Google Cloud Functions (GCF)

There are a few prerequisites. You need:

- A Google Cloud Platform (GCP) project, with billing enabled (although as I mentioned earlier, experimentation with Functions is likely to all come within the free tier)

- The Cloud Functions and Cloud Build APIs enabled

- The Google Cloud SDK (gcloud)

Rather than give the instructions here, I suggest you go to the Java GCF quickstart docs and follow the first five steps of the “Creating a GCP project using Cloud SDK” section. Ignore the final step around preparing your development environment. I’ll update this post when the .NET quickstart is available.

Once all the prerequisites are available, the actual deployment is simple. From the command line:

gcloud functions deploy hello-world --runtime=dotnet3 --entry-point=HelloWorld.Function --trigger-http --allow-unauthenticated

That’s all on one line so that it’s simple to cut and paste even into the Windows command line, but it breaks down like this:

gcloud functions deploy – the command we’re running (deploy a function)hello-world – the name of the function we’re creating, which will appear in the Functions console--runtime=dotnet3 – we want to use the .NET runtime within GCF--entry-point=HelloWorld.Function – this specifies the fully qualified name of the target function type.--trigger-http – the function is triggered via HTTP requests (rather than events)--allow-unauthenticated – the function can be triggered without authentication

Note: if you used a directory other than HelloWorld earlier, or changed the namespace in the code, you should adjust the --entry-point command-line argument accordingly. You need to specify the namespace-qualified name of your function type.

That command uploads your source code securely, builds it, then deploys it. (When I said that having the .NET Core SDK is a prerequisite, that’s true for the template and running locally… but you don’t need the SDK installed to deploy to GCF.)

The function will take a couple of minutes to deploy – possibly longer for the very first time, if some resources need to be created in the background – and eventually you’ll see all the details of the function written to the console. This is a bit of a wall of text, but you want to look for the httpsTrigger section and its url value. Visit that URL, and hey presto, you’re running a function.

If you’re following along but didn’t have any of the prerequisites installed, that may have taken quite a while – but if you’re already a GCP user, it’s really pretty quick.

Personal note: I’d love it if we didn’t need to specify the entry point on the command line, for projects with only one function. I’ve made that work when just running dotnet run, as we saw earlier, but currently you do have to specify the entry point. I have some possibly silly ideas for making this simpler – I’ll need to ask the team how feasible they are.

What’s in a name?

We’ve specified two names in the command line:

- The name of the function as it will be shown within the Functions Console. (This is

hello-world in our example.)

- The name of the class implementing the function, specified using

--entry-point. (This is HelloWorld.Function in our example.)

When I started working with Google Cloud Functions, I got a bit confused by this, and it seems I’m not the only one.

The two names really are independent. We could have deployed the same code multiple times to create several different functions listening on several different URLs, but all specifying the same entry point. Indeed, I’ve done this quite a lot in order to explore the exact HTTP request used by Pub/Sub, Storage and Firebase event triggers: I’ve got a single project with a function class called HttpRequestDump.Function, and I’ve deployed that multiple times with functions named pubsub-test, storage-test and so on. Each of those functions is then independent – they have separate logs, I can delete one without it affecting the others, etc. You could think of them as separate named “instances” of the function, if you want.

What’s going on? Why don’t I need a Main method?

Okay, time for some explanations… at least of the .NET side of things.

Let’s start with the packages involved. The Functions Framework ships four packages:

- Google.Cloud.Functions.Framework

- Google.Cloud.Functions.Hosting

- Google.Cloud.Functions.Testing

- Google.Cloud.Functions.Templates

We’ve already seen what the Templates package provides, and we’ll look at Testing later on.

The separation between the Hosting package and the Framework package is perhaps a little arbitrary, and I expect it to be irrelevant to most users. The Framework package contains the interfaces that functions need to implement, and adapters between them. If you wanted to host a function yourself within another web application, for example, you could depend just on the Framework package, and your function could have exactly the same code as it does otherwise.

The Hosting package is what configures and starts the server in the more conventional scenario, and this is the package that the “normal” functions deployment scenario will depend on. (If you look at the project file from earlier, you’ll see that it depends on the Hosting package.)

While the Hosting package has become a bit more complex over the course of the alpha and beta releases, it’s fundamentally very small considering what it does – and that’s all because it builds on the foundation of ASP.NET Core. I cannot stress this enough – without the fantastic work of the ASP.NET Core team, we wouldn’t be in this position now. (Maybe we’d have built something from scratch, I don’t know. I’m not saying there wouldn’t be a product, just that I really appreciate having this foundation to build on.)

None of that explains how we’re able to just use dotnet run without having a Program.cs or anything else with a Main method though. Sure, C# 9 has fancy features around top-level programs, but that’s not being used here. (I do want to see if there’s something we can do there, but that’s a different matter.)

This is where Project Dragonfruit comes in – inspirationally, at least. This is a relatively little-known project as part of the System.CommandLine effort; Scott Hanselman’s blog post on it sets the scene pretty well.

The cool thing about Project Dragonfruit is that you write a Main method that has the parameters you want with the types that you want. You can still use dotnet run, and all the parsing happens magically before it gets to your code. The magic is really in the MSBuild targets that come as part of the NuGet package. They generate a bit of C# code that first calls the parser and then calls your Main method, and set that generated code as the entry point.

My JonSkeet.DemoUtil NuGet package (which I really ought to document some time) does the same thing, allowing me to create a project with as many Main methods as I want, and then get presented with a menu of them when I run it. Perfect for demos in talks. (Again, this is copying the idea from Project Dragonfruit.)

And that’s basically what the Hosting package in the Functions Framework does. The Hosting package exposes an EntryPoint class with a StartAsync method, and there are MSBuild targets that automatically generate the entry point for you (if the consuming project is an executable, and unless you disable it).

You can find the generated entry point code in the relevant obj directory (e.g. obj/Debug/netcoreapp3.1) after building. The code looks exactly like this, regardless of your function:

// <auto-generated>This file was created automatically</auto-generated>

using System.Runtime.CompilerServices;

using System.Threading.Tasks;

[CompilerGenerated]

internal class AutoGeneratedProgram

{

public static Task<int> Main(string[] args) =>

Google.Cloud.Functions.Hosting.EntryPoint.StartAsync(

typeof(global::AutoGeneratedProgram).Assembly, args);

}

Basically it calls EntryPoint.StartAsync and passes in “the assembly containing the function” (and any command line arguments). Everything else is done by EntryPoint.

We’ll see more of the features of the Hosting package later on, but at least this has answered the question of how dotnet run works with our HelloWorld function.

Testing HelloWorld

Okay, so we’ve got HelloWorld to run locally, and we’ve deployed it successfully… but are we convinced it works? Well yes, I’m pretty sure it does, but even so, it would be nice to test that.

I’m a big fan of “testing” packages – additional NuGet packages to make it easier to use code that works with that core package. So for example, with NodaTime there’s a NodaTime.Testing package, which we’ll actually use later in this blog post. I don’t know where I got the name “testing” from – it may have been an internal Google convention that I decided to use from NodaTime – but the concept is really handy.

As I mentioned earlier, there’s a Google.Cloud.Functions.Testing package, and now I’ve explained the naming convention you can probably guess that it’s going to get involved.

The Testing package provides:

- An in-memory ILogger and ILoggerProvider so you can easily unit test functions that use logging, including testing the logs that are written. (IMO this should really be something available in ASP.NET Core out of the box.)

- A simple way of creating a test server (using Microsoft.AspNetCore.TestHost), which automatically installs the in-memory logger.

- A base class for tests that automatically creates a test server for a function, and exposes common operations such as “make a GET request and retrieve the text returned”.

Arguably it’s a bit unconventional to have a base class for tests like this. It’s entirely possible to use composition instead of inheritance. But my experience writing the samples for the Functions Framework led me to dislike the boilerplate code that came with composition. I don’t mind the bit of a code smell of using a base class, when it leads to simple tests.

I won’t go through all of the features in detail, but let’s look at the test for HelloWorld. There’s really not much to test, given that there’s no conditional logic – we just want to assert that when we make a request to the server, it writes out “Hello, Functions Framework.” in the response.

Just for variety, I’ve decided to use NUnit in the sample code for this blog post. Most of my tests for work code use xUnit these days, but nothing in the Testing package depends on actual testing packages, so it should work with any test framework you want.

Test lifecycle note: different test frameworks use different lifecycle models. In xUnit, a new test class instance is created for each test case, so we get a “clean” server each time. In NUnit, a single test fixture instance is created and used for all tests, which means there’s a single server, too. The server is expected to be mostly stateless, but if you’re testing against log entries in NUnit, you probably want a setup method. There’s an example later.

So we can set up the project simply:

mkdir HelloWorld.Tests

cd HelloWorld.Tests

dotnet new nunit -f netcoreapp3.1

dotnet add package Google.Cloud.Functions.Testing --version 1.0.0-beta02

dotnet add reference ../HelloWorld/HelloWorld.csproj

(I’d normally do all of this within Visual Studio, but the command line shows you everything you need in terms of project setup. Note that I’ve specified netcoreapp3.1 as the target framework simply because I’ve got the preview of .NET 5 installed, which leads to a default target of net5… and that’s incompatible with the function project.)

With the project in place, we can add the test itself:

using Google.Cloud.Functions.Testing;

using NUnit.Framework;

using System.Threading.Tasks;

namespace HelloWorld.Tests

{

public class FunctionTest : FunctionTestBase<Function>

{

[Test]

public async Task RequestWritesMessage()

{

string text = await ExecuteHttpGetRequestAsync();

Assert.AreEqual("Hello, Functions Framework.", text);

}

}

}

The simplicity of testing is one of the things I’m most pleased with in the Functions Framework. In this particular case I’m happy to use the default URI (“sample-uri”) and a GET request, but there are other methods in FunctionTestBase to make more complex requests, or to execute CloudEvent functions.

So is this a unit test or an integration test? Personally I’m not too bothered by the terminology, but I’d call this an integration test in that it does check the integration through the Functions stack. (It doesn’t test integration with anything else because the function doesn’t integrate with anything else.) But it runs really quickly, and this is my “default” kind of test for functions now.

Beyond hello world: what’s the time?

Let’s move from a trivial function to a cutting-edge, ultra-complex, get-ready-for-mind-melting function… we’re going to report the current time. More than that, we’re going to optionally report the time in a particular time zone. (You knew I’d bring time zones into this somehow, right?)

Rather than walk you through every small step of the process of setting this up, I’ll focus on the interesting bits of the code. If you want to see the complete code, it’s in the ZoneClock and ZoneClock.Tests directories in GitHub.

Regular readers will be unsurprised that I’m going to use NodaTime for this. This short function will end up demonstrating plenty of features:

- Dependency injection via a “Function Startup class”

- Logger injection

- Logger behaviour locally vs in GCF

- Testing a function that uses dependency injection

- Testing log output

Let’s start with the code itself. We’ll look at it in three parts.

First, the function class:

[FunctionsStartup(typeof(Startup))]

public class Function : IHttpFunction

{

private readonly IClock clock;

private readonly ILogger logger;

// Receive and remember the dependencies.

public Function(IClock clock, ILogger<Function> logger) =>

(this.clock, this.logger) = (clock, logger);

public async Task HandleAsync(HttpContext context)

{

// Implementation code we'll look at later

}

}

Other than the attribute, this should be very familiar code to ASP.NET Core developers – our two dependencies (a clock and a logger) are provided in the constructor, and remembered as fields. We can then use them in the HandleAsync method.

For any readers not familiar with NodaTime, IClock is an interface with a single method: Instant GetCurrentInstant(). Any time you would call DateTime.UtcNow in DateTime-oriented code, you want to use a clock in NodaTime. That way, your time-sensitive code is testable. There’s a singleton implementation which simply delegates to the system clock, so that’s what we need to configure in terms of the dependency for our function, when running in production as opposed to in tests.

Dependency injection with Functions startup classes

Dependency injection is configured in the .NET Functions Framework using Functions startup classes. These are a little bit like the concept of the same name in Azure Functions, but they’re a little more flexible (in my view, anyway).

Functions startup classes have to derive from Google.Cloud.Functions.Hosting.FunctionsStartup (which is a regular class; the attribute is called FunctionsStartupAttribute, but C# allows you to apply the attribute just using FunctionsStartup and it supplies the suffix).

FunctionsStartup is an abstract class, but it doesn’t contain any abstract members. Instead, it has four virtual methods, each with a no-op implementation:

void ConfigureAppConfiguration(WebHostBuilderContext context, IConfigurationBuilder configuration)void ConfigureServices(WebHostBuilderContext context, IServiceCollection services)void ConfigureLogging(WebHostBuilderContext context, ILoggingBuilder logging)void Configure(WebHostBuilderContext context, IApplicationBuilder app)

These will probably be familiar to ASP.NET Core developers – they’re the same configuration methods that exist on IWebHostBuilder.

A Functions startup class overrides one or more of these methods to configure the appropriate aspect of the server. Note that the final method (Configure) is used to add middleware to the request pipeline, but the Functions Framework expects that the function itself will be the last stage of the pipeline.

The most common method to override (in my experience so far, anyway) is ConfigureServices, in order to configure dependency injection. That’s what we need to do in our example, and here’s the class:

public class Startup : FunctionsStartup

{

public override void ConfigureServices(WebHostBuilderContext context, IServiceCollection services) =>

services.AddSingleton<IClock>(SystemClock.Instance);

}

This is the type referred to by the attribute on the function class:

[FunctionsStartup(typeof(Startup))]

Unlike “regular” ASP.NET Core startup classes (which are expected to configure everything), Functions startup classes can be composed. Every startup that has been specified either on the function type, or its based types, or the assembly, is used. If you need the startups to be applied in a particular order, you can specify that in the attribute.

Only the function type that is actually being served is queried for attributes. You could have two functions in the same project, and each of them have different startup class attributes… along with assembly attributes specifying any startup classes that both functions want.

Note: when running from the command line, you can specify the function to serve as a command line argument or an environment variable. The framework will fail to start (with a clear error) if you try to run a project with multiple functions, but without specifying which one you want to serve.

The composition aspect allows third parties to integrate with the .NET Functions Framework cleanly. For example, Steeltoe could provide a Steeltoe.GoogleCloudFunctions package containing a bunch of startup classes, and you could just specify (in attributes) which ones you wanted to use for any given function.

Our Startup class only configures the IClock dependency. It doesn’t need to configure ILogger, because ASP.NET Core does this automatically.

Finally, we can write the actual function body. This is reasonably simple. (Yes, it’s nearly 30 lines long, but it’s still straightforward.)

public async Task HandleAsync(HttpContext context)

{

// Get the current instant in time via the clock.

Instant now = clock.GetCurrentInstant();

// Always write out UTC.

await WriteTimeInZone(DateTimeZone.Utc);

// Write out the current time in as many zones as the user has specified.

foreach (var zoneId in context.Request.Query["zone"])

{

var zone = DateTimeZoneProviders.Tzdb.GetZoneOrNull(zoneId);

if (zone is null)

{

logger.LogWarning("User provided invalid time zone '{id}'", zoneId);

}

else

{

await WriteTimeInZone(zone);

}

}

Task WriteTimeInZone(DateTimeZone zone)

{

string time = LocalDateTimePattern.GeneralIso.Format(now.InZone(zone).LocalDateTime);

return context.Response.WriteAsync($"Current time in {zone.Id}: {time}\n");

}

}

I haven’t bothered to alert the user to the invalid time zone they’ve provided, although the code to do so would be simple. I have logged a warning – mostly so I can demonstrate logging.

The use of DateTimeZoneProviders.Tzdb is a slightly lazy choice here, by the way. I could inject an IDateTimeZoneProvider as well, allowing for tests with custom time zones. That’s probably overkill in this case though.

Logging locally and in production

So, let’s see what happens when we run this.

The warning looks like this:

2020-10-21T09:53:45.334Z [ZoneClock.Function] [warn] User provided invalid time zone 'America/Metropolis'

This is all on one line: the console logger used by default by the .NET Functions Framework when running locally is a little more compact than the default console logger.

But what happens when we run in Google Cloud Functions? Let’s try it…

gcloud functions deploy zone-clock --runtime=dotnet3 --entry-point=ZoneClock.Function --allow-unauthenticated --trigger-http

If you’re following along and deploying it yourself, just visit the link shown in the gcloud output, and add ?zone=Europe/London&zone=America/New_York to show the London and New York time zones, for example.

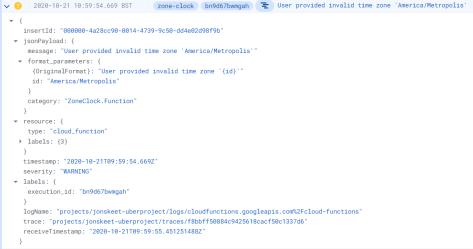

If you go to the Cloud Functions Console and select the zone-clock function, you can view the logs. Here are two requests:

(Click on each image for the full-sized screenshot.)

Note how the default “info” logs are differentiated from the “warning” log about the zone ID not being found.

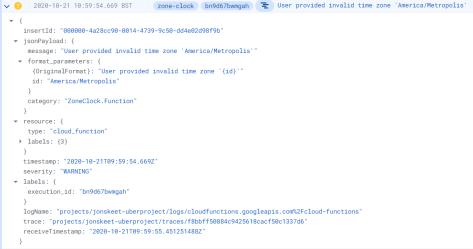

In the Cloud Logging Console you can expand the log entry for more details:

You can easily get to the Cloud Logging console from the Cloud Functions log viewer by clicking on the link in top right of the logs. That will take you to a Cloud Logging page with a filter to show just the logs for the function you’re looking at.

The .NET Functions Framework detects when it’s running in a Knative environment, and writes structured JSON to the console instead of plain text. This is then picked up and processed by the logging infrastructure.

Testing with dependencies

So, it looks like our function does what we want it to, but it would be good to have tests to prove it. If we just use a FunctionTestBase like before, without anything else, we’d still get the production dependency being injected though, which would make it hard to write robust tests.

Instead, we want to specify different Functions startup classes for our tests. We want to use a different IClock implementation – a FakeClock from the NodaTime.Testing package. That lets us create an IClock with any time we want. Let’s set it to June 3rd 2015, 20:25:30 UTC:

class FakeClockStartup : FunctionsStartup

{

public override void ConfigureServices(WebHostBuilderContext context, IServiceCollection services) =>

services.AddSingleton<IClock>(new FakeClock(Instant.FromUtc(2015, 6, 3, 20, 25, 30)));

}

So how do we tell the test to use that startup? We could manually construct a FunctionTestServer and set the startups that way… but it’s much more convenient to use the same FunctionsStartupAttribute as before, but this time applied to the test class:

[FunctionsStartup(typeof(FakeClockStartup))]

public class FunctionTest : FunctionTestBase<Function>

{

// Tests here

}

(In my sample code, FakeClockStartup is a nested class inside the test class, whereas the production Startup class is a top-level class. There’s no specific reason for this, although it feels reasonably natural to me. You can organize your startup classes however you like.)

If you have any startup classes which should be used by all the tests in your test project, you can apply FunctionsStartupAttribute to the test assembly.

The tests themselves check two things:

- The output that’s written to the HTTP response

- The log entries written by the function (but not by other loggers)

Again, FunctionTestBase makes the latter easy, with a GetFunctionLogEntries() method. (You can get at all the logs if you really want to, of course.)

I’ve actually got three tests, but one will suffice to show the pattern:

[Test]

public async Task InvalidCustomZoneIsIgnoredButLogged()

{

string actualText = await ExecuteHttpGetRequestAsync("?zone=America/Metropolis&zone=Europe/London");

// We still print UTC and Europe/London, but America/Metropolis isn't mentioned at all.

string[] expectedLines =

{

"Current time in UTC: 2015-06-03T20:25:30",

"Current time in Europe/London: 2015-06-03T21:25:30"

};

var actualLines = actualText.Split('\n', StringSplitOptions.RemoveEmptyEntries);

Assert.AreEqual(expectedLines, actualLines);

var logEntries = GetFunctionLogEntries();

Assert.AreEqual(1, logEntries.Count);

var logEntry = logEntries[0];

Assert.AreEqual(LogLevel.Warning, logEntry.Level);

StringAssert.Contains("America/Metropolis", logEntry.Message);

}

As a side-note, I generally prefer NUnit over xUnit, but I really wanted to

be able to write:

// Would be valid in xUnit...

var logEntry = Assert.Single(GetFunctionLogEntries());

In xUnit the Assert.Single method validates that its input (GetFunctionLogEntries() in this case) contains a single element, and returns that element so you can perform further assertions on it. There’s no equivalent in NUnit that I’m aware of, although it would be easy to write one.

As noted earlier, we also need to make sure that the logs are cleared before the start of each test, which we can do with a setup method:

[SetUp]

public void ClearLogs() => Server.ClearLogs();

(The Server property in FunctionTestBase is the test server that it

creates.)

Okay, so that’s HTTP functions… what else can we do?

CloudEvent functions

Functions and events go together very naturally. Google Cloud Functions can be triggered by various events, and in the .NET Functions Framework these are represented as CloudEvent functions.

CloudEvents is a CNCF project to standardize the format in which events are propagated and delivered. It isn’t opinionated about the payload data, or how the events are stored etc, but it provides a common “envelope” model, and specific requirements of how events are represented in transports such as HTTP.

This means that you can write at least some code to handle “any event”, and the overall structure should be familiar even if you move between (say) Microsoft-generated and Google-generated events. For example, if both Google Cloud Storage and Azure Blob Storage can emit events (e.g. when an object/blob is created or deleted) then it should be easy enough to consume that event from Azure or Google Cloud Platform respectively. I wouldn’t expect it to be the same code for both kinds of event, but at least the deserialization part of “I have an HTTP request; give me the event information” would be the same. In C#, that’s handled via the C# CloudEvents SDK.

If you’re happy deserializing the data part yourself, that’s all you need, and you can write an untyped CloudEvent function like this:

public class Function : ICloudEventFunction

{

public Task HandleAsync(CloudEvent cloudEvent, CancellationToken cancellationToken)

{

// Function body

}

}

Note how there’s no request and response: there’s just the event.

That’s all very well, but what if you don’t want to deserialize the data yourself? I don’t want users to have to write their own representation of (say) our Cloud Pub/Sub message event data. I want to make it as easy as possible to consume Pub/Sub messages in functions.

That’s where two other repositories come in:

The latter repository provides two packages at the moment: Google.Events and Google.Events.Protobuf. You can add a dependency in your functions project to Google.Events.Protobuf, and then write a typed CloudEvent function like this:

public class Function : ICloudEventFunction<MessagePublishedData>

{

public Task HandleAsync(CloudEvent cloudEvent, MessagePublishedData data, CancellationToken cancellationToken)

{

// Function body

}

}

Your function is still provided with the original CloudEvent so it can access metadata, but the data itself is deserialized automatically.

Serialization library choices

There’s an interesting design issue here. The schemas for the event data are originally in protobuf format, and we’re also converting them to JSON schema. It would make sense to be able to deserialize with any of:

- Google.Protobuf

- System.Text.Json

- Newtonsoft.Json

If you’re already using one of those dependencies elsewhere in your code, you probably don’t want to add another of them. So the current plan is to provide three different packages, one for each deserialization library. All of them apply common attributes from the Google.Events package, which has no dependencies itself other than the CloudEvents SDK, and is what the Functions Framework depends on.

Currently we’ve only implemented the protobuf-based option, but I do want to get to the others.

(Note that currently the CloudEvents SDK itself depends on Newtonsoft.Json, but I’m hoping we can remove that dependency before we release version 2.0 of the CloudEvents SDK, which I’m working on jointly with Microsoft.)

That all sounds great, but it means we’ve got three different representations of MessagePublishedData – one for each serialization technology. It would be really nice if we could have just one representation, which all of them deserialized to, based on which serialization package you happened to use. That’s an issue I haven’t solved yet.

I’m hoping that in the world of functions that won’t matter too much, but of course CloudEvents can be produced and consumed in just about any code… and at the very least, it’s a little annoying.

Writing CloudEvent functions

I’m not going to present the same sort of “hello world” experience for CloudEvent functions as for HTTP functions, simply because they’re less “hands on”. Even I don’t get too excited by publishing a Pub/Sub message and seeing a log entry that says “I received a Pub/Sub message with at this timestamp.”

Instead, I’ll draw your attention to an example with full code in the .NET Functions Framework repository.

It’s an example which is in some ways quite typical of how I see CloudEvent functions being used – effectively as plumbing between other APIs. This particular examples listens for Google Cloud Storage events where an object has been created or updated, and integrates it with the Google Cloud Vision API to perform image recognition and annotation. The steps involved are:

- The object is created or updated in a Storage bucket

- An event is generated, which triggers the CloudEvent function

- The function checks the content type and filename, to see whether it’s probably an image. (If it isn’t, it stops at this point.)

- It asks the Vision API to perform some basic image recognition, looking for faces, text, landmarks and so on.

- The result is summarised in a “text file object” which is created alongside the original image file.

The user experience is that they can drop an image into Storage bucket, and a few seconds later there’s a second file present with information about the image… all in a relatively small amount of code.

The example should be easy to set up, assuming you have both Storage and Vision APIs enabled – it’s then very easy to test. While you’re looking at that example, I encourage you to look at the other examples in the repository, as they show some other features I haven’t covered.

Of course, all the same testing features for HTTP functions are available for CloudEvent functions too, and there are helper methods in FunctionTestBase to execute the function based on an event and so on. Admittedly API-like dependencies tend to be harder to take out than IClock, but the function-specific mechanisms are still the same.

Conclusion

It’s been so much fun to describe what I’ve been working on, and how I’ve tried to predict typical use cases and make them easy to implement with the .NET Functions Framework.

The framework is now in beta, which means there’s still time to make some changes if we want to… but we won’t know the changes are required unless we get feedback. So I strongly encourage you to give it a try, whether you have experience of FaaS on other platforms or not.

Feedback is best left via issues on the GitHub repository – I’d love to be swamped!

I’m sure there’ll be more to talk about in future blog posts, but this one is already pretty gigantic, so I’ll leave it there for now…