Despite this blog series going very slowly, the DigiMixer project itself has certainly not been stalled. Over the last year, I’ve added support for various additional mixers, as well as improving the support for some of the earlier ones, and performing quite a lot of refactoring.

DigiMixer now supports the following mixers, to a greater or lesser extent:

- Behringer X series (tested with XR16, XR18, X-32R) and Midas M series (only tested with M32R, but I expect it to be identical to the X series)

- Harman Soundcraft Ui series (tested with Ui24R)

- Allen & Heath Qu series (tested with Qu-SB, including the AR84 stage box)

- Allen & Heath CQ series (tested with CQ-20B)

- RCF M-18

- Mackie DL series (tested with DL16S and DL32R, which proved significantly difference)

- Yamaha DM series (tested with DM-3)

- PreSonus StudioLive Series III (tested with 16R)

In order to support each mixer, we have to be able to communicate with it. The only sort of “standardised” protocol used by the above mixers is OSC (Open Sound Control) – and that’s still only a matter of standardising what an OSC message looks like, not what the various addresses and values mean. Some mixers support MIDI to a certain extent, sometimes even with documentation around how that support works. (Again, there’s no one standard for how MIDI integration in a mixer “should” be implemented – it’s not like MIDI on actual instruments where you can reasonably expect a given MIDI message to mean “play middle C”.) That’s useful in terms of integration within a DAW, but none of the mixers I’ve seen so far provide sufficient control via MIDI to meet DigiMixer’s needs.

This post will go into a little detail about the protocols I’ve encountered so far, what we actually need for DigiMixer, and some practical aspects of how I’ve been reverse engineering the protocols.

I’m hoping to start writing more detailed documentation about each protocol within the GitHub repo, in the Protocols directory. There’s a bit of information about the Mackie DL series at the moment, with more to come when I find time. It’s worth being aware that any terminology I use within that directory is likely to be entirely unofficial – when I talk about a message “chunk size” or “subtype” etc, that’s just what I’ve used in the code for lack of a better term.

Very high level categorizations

Let’s start with the very highest levels of categorization for the protocol: everything DigiMixer supports uses the network to communicate, and all over IP. There may well be some digital mixers where the client/mixer connection is over USB, and as I mentioned before it’s also possible to control some mixers to some extent using MIDI (which could be via a USB-MIDI connection, dedicated MIDI hardware, or even MIDI over IP) – but I haven’t investigated any mixer protocols that aren’t network-oriented.

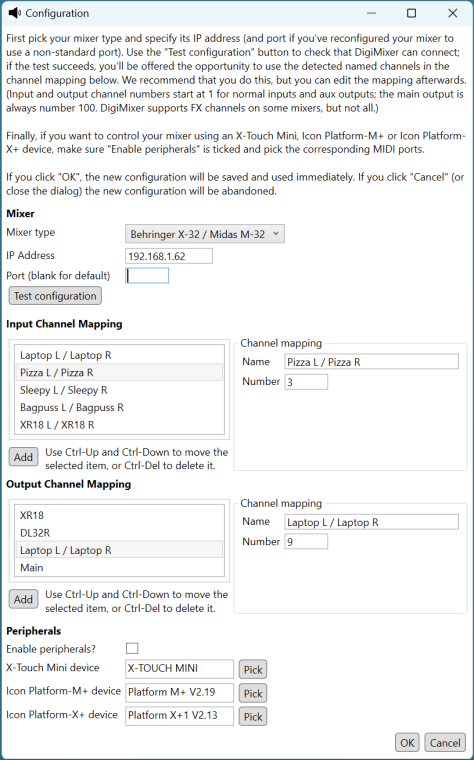

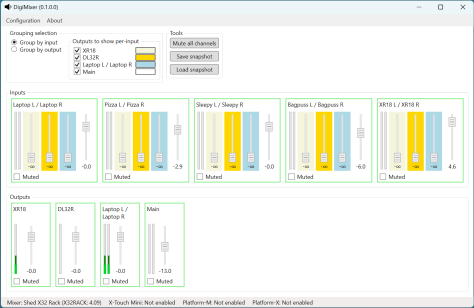

It’s worth being really clear about the difference between the “client/mixer” protocol and any “client/control surface” protocols. In the same repository as DigiMixer, I have some libraries for integration with the Icon Platform and X-Touch Mini control surfaces – both of which are integrated with DigiMixer via an application (which currently isn’t on public GitHub, unfortunately, as it shares configuration with At Your Service). One of the purposes of the abstraction of DigiMixer is to allow mixers to be treated as broadly interchangeable – so the same DigiMixer-based code that controls (say) a CQ-20B using an X-Touch Mini should be able to control an X32 with no changes. This post ignores the control surface aspects entirely, other than in terms of what we want to be able to do with DigiMixer, focusing on the client/mixer protocols.

The most obvious initial categorization of the protocols is in terms of transport (OSI layer 4) protocol: in our case, always UDP or TCP, or a mixture.

One fairly common pattern (used by the CQ, DM, Qu, StudioLive mixers) is to have a TCP connection for control aspects, but report meter levels over UDP. Meters show the point-in-time sound level for a particular input or output; typically it doesn’t matter if a meter packet is dropped every so often – so it makes sense to use UDP for that. It’s obviously rather more important if a “mute this channel” message is dropped, so the reliability of TCP is useful there.

The RCF M-18 and the X/M series of Behringer/Midas mixers use OSC over UDP. (The DM-3 also supports OSC over UDP, but doesn’t expose enough functionality to meet DigiMixer’s requirements.) The unreliability of UDP is worrying here; presumably the expectation is that you only operate them on sufficiently reliable networks that it’s not a problem, or that clients request “current state” peridiocally from the mixer and check it for consistency with their own expected state. My experience is that on a wired network with just a single switch between the mixer and the client (which would be the common deployment scenario), it’s never actually caused a problem.

The DL and Ui series only use TCP as far as I’ve seen (or at least as far as DigiMixer is concerned). The Ui series is particularly interesting here; its manufacturer-provided user interface is just a web UI. The mixer’s built-in web server serves the user interface itself, which connects back to the mixer still on port 80 to create a web socket connection. I don’t know enough about web socket standards to know how “normal” the implementation is, but it’s very simple to code against: issue a request of “GET /raw HTTP1.1”, read the response headers, and then it’s just a line-oriented protocol. Each message within the protocol (in both directions) is an ASCII line of text. I’ll come back to message formats later on.

Sources of information

Working on DigiMixer has been a fascinating exercise in piecing together information from multiple sources. Typically the implementation of each protocol has been relatively straightforward when I’ve had enough information of the protocol itself, but that information is hard to come by.

In some cases, the manufacturer has provided the information itself, either officially or unofficially. For the Ui series for example, Harman support responded to my enquiry really quickly, sending me documentation which was, while not fully comprehensive, easily enough to get started with. (They did stress that this documentation was in no way a guarantee of future compatibility or support.)

In other cases, there’s an active community with really strong efforts, including a mixture of official and unofficial documentation. The Behringer X series and Midas M series (which are basically the same in terms of software, as far as I can tell) have lots of active projects to access them via OSC, and the most comprehensive documentation comes from Patrick-Gilles Maillot’s site.

For the StudioLive mixers, there’s a GitHub project and documentation which are strictly unofficial and still at least somewhat incomplete – but invaluable. The situation is similar for the RCF M-18, where a single inactive GitHub repo is basically I could find.

For other mixers… there’s Wireshark. All the digital mixers I’ve looked at have manufacturer-supplied clients. When those run on Windows, it’s easy to just start Wireshark, open the client and (say) move a fader, then close the client and look at the traffic between the mixer and the client. Things are slightly more fiddly if the only client provided is an Android or iOS app, but I’ve found the TP-Link TL-SG105E to be really handy – it’s a small, silent, managed switch which supports port mirroring. So all I need to do is plug both my laptop and the mixer into the switch, mirror traffic from the mixer port to the laptop port, and again run Wireshark.

Mixing Station supports all of these mixers too, and sometimes it’s useful to look at the traffic between that and the mixer and compare it with the traffic between the manufacturer-supplied client and the mixer.

Of course, capturing the traffic between the mixer and the client doesn’t generally explain that traffic at all. We don’t need to understand all the traffic though – only enough for DigiMixer to be effective. So what does that consist of?

DigiMixer requirements for protocol comprehension

As I’ve said before, DigiMixer doesn’t try to be a full-fidelity mixer client. It only aims to provide control in terms of muting and unmuting, and moving faders (for either “overall output” or an “input/output combination” so “aux 1 level” or “input 2 level to aux 3” for example). Additionally, it attempts to provide information about channel names, general mixer information, any channels that are linked together to form stereo pairs, and meter information.

In protocol terms, that normally means we need to understand:

- Initial connection requirements, including any “client handshake”. (For mixer TCP + UDP protocols, this handshake over TCP sometimes involves each side telling the other which UDP port they’re listening on.)

- How to fetch mixer information (model, version, user-specified mixer name)

- How to fetch the initial state of the mixer (channel names, any stereo links, and current fader/mute status)

- How to send “mute/unmute this channel” and “move this fader” commands

- What the mixer sends to the client if state is changed by another client

- What the mixer sends to the client to report meter levels (potentially including how the client requests these in the first place)

Some protocols make those requirements very easy to fulfil – others are significantly more challenging.

Protocol layers and steps in reverse-engineering a protocol

I’ve never fully understood the OSI model, in terms of being able to clearly place any specific bit of a protocol into one of the seven layers. However, the idea of layering in general has been very useful within DigiMixer. Most of the implementations for mixers are implemented as two projects, one with a “core” suffix and one without, e.g. DigiMixer.Mackie.Core and DigiMixer.Mackie. The “core” project in each case is focused around what I expect would be the presentation layer (and sometimes the session layer) in OSI; I think of it in terms of message framing then message decomposition. (I believe that I’m using message framing in a perfectly standard way here. There’s probably a better name for message decomposition.)

All of the protocols used by DigiMixer have the idea of a message:

- TCP connections form a bidirectional stream of messages

- Each UDP connection forms a unidirectional stream of messages

(In some protocols the mixer uses UDP connections bidirectionally too – basically sending packets to whichever UDP port was used to send packets to it. In other protocols the two UDP streams are entirely separate.)

Message framing

With the UDP protocols I’ve seen implemented when working on DigiMixer, each UDP packet corresponds exactly to one message. There are never UDP packets which contain multiple messages, and a message never needs to be split across multiple packets.

With TCP, however, it’s a different story. Wireshark allows you to follow a TCP stream, showing the flow of data in each direction, but it takes a bit of work to figure out how to split each of those streams into messages.

Here’s part of the traffic I see in Wireshark when opening the DM-3 MixPad app in Windows, for example.

00000000 4d 50 52 4f 00 00 00 1d 11 00 00 00 18 01 01 01 MPRO.... ........

00000010 02 31 00 00 00 09 50 72 6f 70 65 72 74 79 00 11 .1....Pr operty..

00000020 00 00 00 01 80 .....

00000025 4d 50 52 4f 00 00 00 47 11 00 00 00 42 01 10 01 MPRO...G ....B...

00000035 04 11 00 00 00 01 00 31 00 00 00 09 50 72 6f 70 .......1 ....Prop

00000045 65 72 74 79 00 11 00 00 00 10 3a 7c 8d 4c 85 f8 erty.... ..:|.L..

00000055 9f 1e aa 83 4f 96 63 0c ec 3d 11 00 00 00 10 8b ....O.c. .=......

00000065 76 f3 98 78 64 6e 83 15 f5 81 7c 06 cc b6 91 4d v..xdn.. ..|....M

00000075 50 52 4f 00 00 00 09 11 00 00 00 04 01 04 01 00 PRO..... ........

00000000 4d 50 52 4f 00 00 00 47 11 00 00 00 42 01 10 01 MPRO...G ....B...

00000010 04 11 00 00 00 01 00 31 00 00 00 09 50 72 6f 70 .......1 ....Prop

00000020 65 72 74 79 00 11 00 00 00 10 3a 7c 8d 4c 85 f8 erty.... ..:|.L..

00000030 9f 1e aa 83 4f 96 63 0c ec 3d 11 00 00 00 10 87 ....O.c. .=......

00000040 49 a1 3e 61 58 ea ce dc 00 0a cb 7d a1 dd cb I.>aX... ...}...

0000004F 4d 50 52 4f 00 00 00 09 11 00 00 00 04 01 04 01 MPRO.... ........

0000005F 00 4d 50 52 4f 00 00 08 c3 11 00 00 08 be 01 14 .MPRO... ........

I suspect that the line break after the third line (between bytes 00000024 and 00000025 outbound) is due to a packet boundary, but it’s also possible that Wireshark is doing a little bit more than that, e.g. only showing a line break between packets if the gap between them (in terms of time) is above some threshold. I’ve generally ignored that, whereas “conversations” of short messages tend to make message boundaries fairly clear.

In this case, the repeated “MPRO” text at least appears at first glance to indicate the start of a message. The four bytes after that “MPRO” then seem to show (in big-endian order) the length of the remainder of the message.

In other words, after looking at a reasonable amount of data like the dump above, I was able to guess that the DM3 protocol had a message framing of:

- 4 bytes: Message type (e.g. “MPRO”, “EEVT”, “MMIX”)

- 4 bytes: Message body length, big-endian

- Message body

A message framing hypothesis like that is reasonably easy to test, particularly after writing a bit of code to parse the text format of a Wireshark hex dump like the above. (My experience is that the text format is generally easier than having to deal with than the full pcapng files that Wireshark deals with by default. The amount of manual work required to follow the TCP stream and then save that as text is pretty small.)

Most of the protocols I’ve worked with have had some sort of “message header, message body” format, where the header includes information about the length of the body. There are some differences though:

- Sometimes there’s some additional state (e.g. a “message counter byte”)

- Sometimes the message header has no information other than framing, unlike the example above, where you really still need to keep the “MPRO” part as the “message type” – not that we know what “type” really means yet

- Sometimes there’s a trailer (e.g. a checksum)

- Sometimes the length information in the header is message length rather than bdoy length (i.e. the length can include or exclude the header itself, depending on the protocol)

In the case of the Ui series, the framing is just based on line breaks instead. These two schemes – “message delimiters” (line breaks) or “headers with length information” – are the main approaches to message framing that I’ve seen, not just in DigiMixer but over the course of my career. (It’s not clear whether you’d include the “single message per UDP packet” or “close the TCP connection after each message” message framing schemes, or just approaches that mean you don’t need message framing at all.) Some protocols have a mixture of the two: HTTP/1.1 uses delimiters for headers, then specifies a content length within one of the headers to allow further requests or responses to be sent on the same connection.

Once I’ve validated a message framing hypothesis in quick-and-dirty code (typically in another project with a Tools suffix, e.g. DigiMixer.Mackie.Tools) I’ll then add that framing into the “core” project, in the form of a message type implementing IMixerMessage:

public interface IMixerMessage<TSelf> where TSelf : class, IMixerMessage<TSelf>

{

static abstract TSelf? TryParse(ReadOnlySpan<byte> data);

int Length { get; }

void CopyTo(Span<byte> buffer);

}

The addition of this interface into DigiMixer was a relatively new feature, as I was waiting for .NET 8 to land. It was predated by the concept of a “message processor” which effectively converts a stream of bytes into a stream of messages in a suitable form for consumption, but prior to the interface with its fun static abstract TryParse method, I had to specify various aspects of the message separately. Between the message interface, the message processor, and a couple of base classes, I now hardly have any code dealing with TcpClient and UdpClient directly. Lovely. (There are now multiple derived classes with hardly any behaviour, and I might refactor those at some point, but at least the logic isn’t repeated.)

Message decomposition

Confirming that I’ve understood the message framing for a protocol is immensely satisfying, and a necessary first step – but it also tends to be the simplest step. It’s often feasible to understand the message framing without understanding the whole of the message header, just as in the above example we don’t know what the different message types mean, or even how many message types there are. More importantly, even if we completely understand the framing, it doesn’t tell us anything about the meaning of those messages. They’re just blobs of data.

Message decomposition goes slightly further, taking the message body apart in terms of its constituent parts – potentially still without understanding the actual meaning of any values.

To take the DM-3 example shown above a bit further, it turns out that every message body that I’ve seen consists of:

- Byte 0x11

- 4 bytes, again a big-endian integer representing a length

- That length in terms of bytes, as the “real” body

That’s just an extra (and redundant as far as I can tell) layer of wrapping, but within the “real” body we have a 4-byte set of flags (which do have some pattern to them, but I haven’t fully figured out) then a sequence of useful data in segments. Each segments consists of:

- A type byte (always 0x11, 0x12, 0x14, 0x24 or 0x31 as far as I’ve seen); more on this below

- The number of “units” being represented

- The units themselves

The type byte consists of two nybbles – the first is the “kind” of units (1 for unsigned integers, including bytes; 2 for signed integers; 3 for characters) and then a second for “the number of bytes per unit”. So 0x11 is just a sequence of bytes, 0x12 is “a sequence of UInt16 values”, 0x14 is “a sequence of UInt32 values”, 0x24 is “a sequence of Int32 values, and 0x31 is basically “a string” (which is null-terminated despite also having a length, but hey).

The segments occur one after another, until the end of the “real” body.

So for the piece of hex shown earlier from the DM-3 (including a large message that was truncated), we can decompose those messages into:

=> MPRO: Flags=01010102; Segments=2

Text: 'Property'

Binary[1]: 80

=> MPRO: Flags=01100104; Segments=4

Binary[1]: 00

Text: 'Property'

Binary[16]: 3A 7C 8D 4C 85 F8 9F 1E AA 83 4F 96 63 0C EC 3D

Binary[16]: 8B 76 F3 98 78 64 6E 83 15 F5 81 7C 06 CC B6 91

=> MPRO: Flags=01040100; Segments=0

<= MPRO: Flags=01100104; Segments=4

Binary[1]: 00

Text: 'Property'

Binary[16]: 3A 7C 8D 4C 85 F8 9F 1E AA 83 4F 96 63 0C EC 3D

Binary[16]: 87 49 A1 3E 61 58 EA CE DC 00 0A CB 7D A1 DD CB

<= MPRO: Flags=01040100; Segments=0

<= MPRO: Flags=01140109; Segments=9

Binary[1]: 00

Text: 'Property'

Text: 'Property'

UInt16[*1]: 0000

UInt32[*0]:

UInt32[*0]:

UInt32[*1]: 000000f0

Binary[2164]: 4D 4D 53 58 4C 49 54 00 50 72 6F 70 65 72 74 79 [...]

Binary[0]:

(My formatting is somewhat inconsistent here – I should probably get rid of the “*” in the lengths for UInt16/UInt32/Int32, but it doesn’t actually hurt the readability much… and this is just the output of a fairly quick-and-dirty tool.)

There’s still no application-level information here, but we can see the structure of the traffic – which makes it much, much easier to then discern bits of the application level protocol.

Application level protocol

Nothing I’ve described so far is mixer-specific. At some point, some combination of message type, flags and values has to actually mean something. Maybe it’s “please send me the version information about the mixer” or “this is the meter levels for the inputs” or “please mute the connection from input channel 1 to output channel 5”.

The process of reverse engineering the application level protocol involves both inspiration and perspiration – usually in that order, and only after working out at least a large proportion of the message framing and message decomposition. You don’t need to know everything, but you do need to know “if I move a fader on the mixer with a different client, I get a message back looking something like X.” That takes experimentation and some leaps of faith. But then you need to carefully document “well, what’s the difference between moving the fader for input 1, output 1 or moving the fader for input 2, output 5, or just an output fader?” – and “what’s the difference between moving the fader from the bottom of its range to a bit higher, and moving it a bit higher still?” That’s somewhat tedious, but still surprisingly rewarding work – so long as you can pay enough attention to transcribe your results to a log carefully enough.

I’m not going to attempt to describe (here) what the various protocols look like at an application level, because they vary so much (even if the lower abstraction levels are reasonably similar) – and because there’s so much I still don’t understand about them. Once I’ve written up some details, they’ll be on GitHub. But understanding how those abstraction levels work at all that’s been really interesting to me – and which I suspect will find useful in entirely different scenarios.

What’s next?

I think after diving into some of the slightly lower level bits of DigiMixer, the next post should probably be at a very high level, and back towards the goal of the whole blog series: abstraction. Assuming I don’t get distracted by something else to write about, I’ll try to make the next post as simple as “what do mixers have in common, and where do they differ, within the scope of DigiMixer?” After that, maybe the following post will be about what that abstraction looks like in code, and some of the trade-offs I’ve made along the way.